“Am I?” I inquire. I thought I was about to be leaving Albania’s capital, Tirana, and heading south to a winery and vineyard near the border with Greece, about a three-and-a-half-hour drive away. I’m keen to check the progress of my 2023 red blend – Albania’s first premium red featuring an indigenous grape variety.

“There’s been a change of plan. It happens,” she says, smiling.

‘It happens’ is a phrase I’ve heard a lot during this wine project, which began in 2022 with the idea of making six wines from lesser-known grape varieties in four countries in one vintage and writing about the experiences for Canopy.

When I started my adventure in Eastern Europe, I thought it was such a great idea that I couldn’t believe no-one else had done something similar. Now, of course, I’m thinking differently.

The problems I encountered en route were nothing compared with the difficulty in selling this limited-edition range of niche wines. But I’m hoping that will change when they make their debut at the CEE Wine Fair, in St John’s Waterloo, London, on Monday, June 9. It could happen. Who knows? More than 300 buyers and journalists turned up for the inaugural event last year and organiser Zsuzsa Toronyi tells me: “Interest in Central and Eastern European wines continues to grow within the trade, as reflected in strong registration numbers. We’re anticipating a busy and engaging event.”

The things that unite my range are low intervention, low sulphites, lesser-known grape varieties (such as Viktória Gyöngye, Kisi, Laški rizling, Muscaris and Blaufränkisch), high quality, handmade, and distinctive. And they’re all from countries in what I believe is the most exciting region for wine – Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Wine expert Caroline Gilby MW, who curates the wines for the CEE event, agrees: “I truly believe that CEE is the most exciting part of the wine world – the pace of change has been nothing short of revolutionary, so today’s winemaking is up there with the best anywhere. But it’s about more than just winemaking technology as these are all countries with a very long history of wine, and wine is deeply embedded in their cultures, and there are many unique grape varieties that connect to place and showcase each country’s distinctive differences. The region is awash with human interest too – passionate people rebuilding their family legacy or falling in love with wine to create new stories.”

The prospect of telling these stories with firsthand experiences was the initial spark which ignited my crazy harvest adventure in 2022, after being starved of travel during the Covid pandemic.

But things have not run as smoothly as I’d hoped. The vines have been hit by hail, the grapes have succumbed to mildew, yields have been low because of the summer heatwave and autumn rain... Plans have been upended at short notice. “It happens.”

And wines have disappeared or dropped off the radar!

I rang a winemaker to check on the condition of my foot-stomped, hand-plunged Blaufränkisch, inquiring if it was ready to be racked to a barrique, only to be told it’s already gone into a large barrel with the rest of the Blaufränkisch from that vintage.

I attempted to be the first to make a Kadarka from three different regions in Hungary, using three different producers and technologies (steel, oak and Flexcube). The first producer informed me that, unfortunately, the bought-in grapes were not the right quality for this project. “It happens.” I understand. A Kadarka from two producers in regions that harvest two weeks apart could also be interesting, I reasoned.

But, after a year, the second producer sent me a message to say my wine had been bottled. I politely explained (again) the whole point was to create a multi-region blend – something different to what was already in their portfolio and something new and exciting for the market. Concepts and creative ideas, it seems, easily get lost in translation. It happens. Much more than I expected.

However, I’m very pleased and excited about the wines that made it all the way to bottle. I’m calling them the most interesting, distinctive and unusual collection of wines from one producer. The very first tasting was for the sommeliers at a Michelin three-star restaurant in Italy (above). I’ve set the bar high for where I see my wines being served.

The first consumer tasting was a seven-course dinner at a restaurant in Sussex, England (below). Diners described it as a “fantastic” evening as it gave them the chance to taste grapes they never knew existed. But sales have been low and slow.

So, on the eve of the range’s big UK launch, I’m reflecting on the things I’ve learned during this project, which is due to continue this year with white wines in Spain (a Forcada) and Ukraine (a Telti-Kuruk), and a Madeira featuring Terrantez. This will give the on-trade a complete line-up of exciting alternatives in all wine categories.

As I round up the samples from my collaborators (some of the most talented winemakers in CEE), I remain convinced there is a market for a unique range of small-batch wines featuring indigenous grapes that have been raised into fine wines with a little experimental winemaking. But the questions keep coming…

Why is it so hard to make money out of wine?

I never expected to make a fortune from this project, but I did expect to recoup my expenses. I’m not sure that will happen. I’ve done a few tastings with critics and influencers, and the feedback on the wines has been uniformly positive. They are surprised by the quality of these relatively unknown grapes and the fact that I have been able to put together such a fascinating range of wines.

I’ve also done a few tastings with somms and independent retailers, but I’ve found it so hard to get wine businesses to make a commitment. They don’t say no, but they don’t say yes either. Is this normal? Or is this where a wine fair comes into its own? We will see.

It’s frustrating because I’ve heard so many times that what the trade wants are top-quality, distinctive wines. That’s what I’m offering. I thought they would be excited to buy such a range, so they could offer something exclusive to their customers and take them on a journey of discovery.

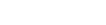

Interestingly, the first wine out of the blocks – a modern amber wine from Georgia (above) – is selling reasonably well in a Georgian-owned wine bar in Peckham, London. The irony is that Peckham is most famous in the UK for a sitcom called Only Fools and Horses, in which one of the catchphrases is: “This time next year, we'll be millionaires!”

It happens, but probably not in my case and not with this project. After 25 years, the TV brothers did become millionaires – by finding and auctioning a rare watch! Time will tell.

The retail prices for my limited-edition wines, I think, are fair. So, I don’t think that’s the issue. They range from £18 for the rosé (a single-vineyard Kékfrankos, fermented and aged in oak) to £60 for a handcrafted sparkling wine featuring the unique pairing of Pearl of Victoria and Grüner Veltliner.

Do I need to think more ‘commercially’ and go for some easier sales?

After producing ultra-niche wines in 2022 and 2023, last year I felt it was time to produce something a little more commercial: the collection’s first rosé. A premium rosé from Hungary. With the family-run winery Gál Szőlőbirtok (above) on Csepel Island (near Budapest), we have produced ‘a serious gastronomic rosé’ – a single-vineyard Blaufränkisch/Kékfrankos with two hours’ skin contact, fermented and aged in oak for five months with weekly bâtonnage for the first four and a half months. This wine was bottled a few weeks ago and will be ready for release this summer.

There was only one barrel, so we only have 400 bottles. I think it’s a lovely dark-pink rosé with wonderful strawberry flavours and a creamy texture. But will this rosé be enough to turn this project from red to black? Let’s hope it happens.

Why do so many wine lovers overlook the hidden gems of Central and Eastern Europe?

I started the project to raise the profiles of grape varieties that I love and think deserve a chance to shine in a top-class wine. These include Kisi and Khihkvi in Georgia, Muscaris and Souvignier Gris in Austria, Laški rizling and Rumeni Plavec in Slovenia, Pugnitello in Italy, Debine e Zezë and Mavrud in Albania, and Blaufränkisch in Slovenia and Hungary.

As Gilby says of the region: “Increasingly, winemakers are moving beyond relying on winemaking technology and barrels but now have the confidence to let place and variety shine. And often this is local grapes that have found a new lease of life when treated with respect rather than as workhorses – grapes that really connect to a place.

“There’s incredible diversity of grapes – thanks to the region’s position as a bridge between east and west as grapes travelled west from the domestication centres in the Caucasus and near East so lots of unique varieties that are often very local but can be flagships for their places.”

One of the most exciting finds is the hybrid grape Pearl of Victoria (Viktória Gyöngye, a Hungarian crossing of Seyve-Villard 12375 and table grape Pearl of Csaba). Its potential for producing high-quality traditional-method fizz is enormous. I blended the Pearl of Victoria with 50% Grüner Veltliner (half of which was fermented and aged for six months in oak). No-one has done this before, but the result is a very classy sparkling wine from Etyek, Hungary’s first PDO for sparkling wines – although neither of these varieties is allowed in the top category Etyeki Pezsgő wines. Being a hybrid, the Pearl of Victoria grapes were sprayed 50% less than the varieties permitted in the Etyek-Buda PDO – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc. It makes a refreshingly lovely change to sip a sparkling wine that isn’t made from Chardonnay, Pinots or Glera.

Sparkling wine producers around the world should take a look at this variety.

How can I get people excited about a DRV’s eco-friendly credentials?

I naively thought that I would be able to sell my amber wine from Austria on its benchmark eco-friendly credentials. The grapes were only sprayed twice during the challenging growing season of 2022; each pass using only about 10% of the copper and sulphur sprayed on organic Chardonnay grapes in a nearby vineyard. Soil analysis at the end of the season revealed no copper toxins in the soil. But, during tastings, the focus always shifts to its ‘natural’ and ‘orange’ elements.

During a recent event, while describing the wine, I realised it covers three of the most divisive categories in the sector: natural, orange, hybrid. How did that happen?

But I love this wine. And one influencer described it as the best orange wine she’d ever tasted. I’m now trying to push it with the term DRV, believing DRV (short for disease-resistant variety) is a more user-friendly term than PIWI (PilzWiderstandsfähig). I know it’s going to be a tough sell, but I still think I can make things happen with this wine. Show me one that tastes better and is more sustainably produced.

Is clay king?

I’m especially pleased with all the wines produced in clay.

For the Austrian amber wine, we put the DRV grapes in amphora, oak and stainless steel. But the final blend of 85% Muscaris and 15% Souvignier Gris is all from amphorae (above). The Muscaris from amphora simply shone, so we blended it with a little Souvignier Gris from amphora to make the wine a little more interesting, complex and subtle.

This project also inspired the addition of amphora to a red-wine project in Tuscany which aims to promote the revival of the ancient grape Pugnitello. After the CEE fair, I will be returning to San Felice (below) to see how it is developing compared to the Pugnitello in steel and the more traditional oak barrels.

The first wine released – and the only one currently on sale in the UK – was made in a qvevri. A fascinating experience: going to Georgia to learn about the ancient art of winemaking in qvevri firsthand.

Qvevris are such brilliant vessels for skin-contact wines; it’s obvious why they have stood the test of time and are undergoing a revival.

The idea behind my Kisi and Khikhvi co-fermentation was to combine traditional Georgian winemaking (a qvevri buried in the ground, six months of skin contact) with modern reductive winemaking techniques to retain the lovely aromas and flavours of the two indigenous Kakheti grapes. So, the qvevri was chilled to -1°C to receive the grapes; after a couple of days of manual punchdowns (below), we used netting and French oak staves fanned out like the spokes of a bicycle wheel to keep the cap submerged for the rest of the fermentation; after which the qvevri was sealed with glass and silicone; and the headspace was filled with nitrogen to prevent oxidation.

It’s quite tannic and will probably be at its peak in a few years. At a recent tasting at 67 Pall Mall in London, it was lined up against a Gravner from 2016 that was four to five times more expensive. But I can see the direction of travel for my wine and I’m telling potential buyers to purchase a case of six so they can drink one a year and track its evolution.

Why is it more difficult to do something different with white grapes?

The initial range comprises a sparkling wine, rosé, three amber wines and a red. There are currently no white wines in my portfolio. My attempts at making a white wine in Croatia using one of its many wonderful indigenous grape varieties have been thwarted by the weather and small yields. My attempts at making a white wine in Ukraine have been thwarted by language barriers. Because my project is so unique, it is hard to explain it to those who don’t have a complete grasp of English.

A white wine project in Spain to help promote the ancient grape Forcada has been postponed a couple of times because of poor vintages. This year, however, I’m hoping to produce a Forcada in association with biodynamic producer Parés Baltà in the Penedès region. But, so far, the best expressions of this indigenous variety are from stainless-steel tanks. Experiments in oak and amphora have not worked so well. The name of my brand is Crazy Experimental Wines. The wine production needs to have an element of experimentation. So, what am I going to do? Let’s see what happens this vintage.

After visiting Ukraine twice to make wine since the full-scale invasion by Russia – and being thwarted more by misunderstandings than the ongoing war – I’m still hoping to make a white wine there. It’s a fascinating country with some excellent indigenous varieties. With my attempts at producing a Sukholimanske in Odesa and a Bakator in the Zakarpattia region failing, I have set my sights on a Telti-Kuruk. The producer speaks excellent English. The only issue is the proximity of the vineyard to the frontline.

Should I shift the focus from skin-contact wines?

Five of the six wines feature an element of skin contact. From two hours to six months. Two hours for the rosé is reasonable and 30 days for the Slovenian red (80% Blaufränkisch) is understandable. But three of the six wines are amber. Skin contact for these wines is from 20 days to six months. The wines, however, are very different:

- “Kisi me slowly, gently” – a Kisi and Khikhvi co-fermentation made in a qvevri in Georgia, with six months’ maceration.

- “DRV #1” – a blend of two disease-resistant varieties from Austria. The 85% Muscaris was left on skins for 20 days. The 15% Souvignier Gris underwent an unusual vinification: about 70% of the skins were removed during the fermentation, as they floated to the top, but the berries that sank were left among the gross lees for more than two years. This helped to protect the wine with only a little sulphur added prior to bottling. Unfined and unfiltered.

- “Oh, natural!” – another low-intervention skin-contact wine. This one, from Slovenia’s northeast, is a pimped-up Laški rizling – a co-fermentation with whole Traminer berries. The Traminer berries spent 28 days in contact with the free-run from the Laški (Welschrielsing, Riesling Italico). It matured on lees in used oak for a couple of years. Again, the only thing added was a little SO2 prior to bottling.

Why did I think social media would be more effective?

Social media isn’t turning out to be as great a sales tool as I was expecting. I’ve garnered a reasonable amount of publicity for this new project, but apart from one expression of interest from a wine bar and shop in Budapest wanting to stock the Hungarian sparkling and rosé, the publicity hasn’t led to any direct sales.

I still feel I need to pump out posts, but don’t have the same enthusiasm.

The most effective sales method so far is the old-fashioned face-to-face meeting with people I know. But I don’t know as many adventurous decision-makers as I thought. That's why I’m going to the the Ultimate CEE Wine Fair. I think the buyers there will be more open-minded. We will see what happens...

Staying in Tirana an extra night, I dine at a modern restaurant flourishing its Michelin-star ambitions. The food is excellent, the ambience is exceptional, and the staff are exemplary. They are keen to learn more about my Albanian red featuring Debine e Zezë and Mavrud (above) and my wine project.

They are eager to try samples. I explain that stock is extremely limited and the only chance to try the current range of six wines is to visit St John’s Waterloo on Monday, June 9. I will be pouring my wines there from 1-4pm only. See you there! Let’s make something good happen.

.png)