Stem percentages

How does one decide what percentage of stems to use? Why would you use more in one vintage than another?David Croix of Domaine des Croix in Beaune, Burgundy, decides based on two primary factors: the ripeness of the vintage and how stems typically work with that terroir. “The riper the vintage is, the more stems I like to add to balance out the ripeness. It’s a combination of the sweetness of the fruit and the vegetal/floral aspect of the stems.”

David rarely goes above 50% stem inclusion. “I can use no stems in less ripe vintages, and 30-50% in riper vintages.”

'There is better integration of stems with red clayish soils'The terroir he is working with is a critical factor in determining what percentage he uses. He feels that “there is better integration of stems with red clayish soils than with white soil loaded with limestone.” Finally, he also considers the ratio between berries and stems. “The quality of the flowering will impact millerandage. If there’s a lot of millerandage, the ratio between berries and stems will change, and you will have to be careful not to use too many stems.”

This is an example of how one winemaker determines stem percentage, but from it, you can infer that every winemaker’s choice about stem percentage will be unique for each individual wine they make, owing to vintage variation, site differences, as well as personal preference.

Make sure you read part 1 of this article for what stems do to a wine chemically, as increasing percentages will have a greater impact on tannin, acid and colour, which may play an important role in the decision (and microbial stability, in the case of acid). Developing a fine-tuned formula for your wines based on your specifics is something that can only be developed through trial and error, or speaking with those working with similar sites.

'I’ve yet to come across much evidence that stems are ever very lignified'

Lignification

One topic that often comes up in stem debates is “stem ripeness” or how lignified (browned and hardened) a stem is at the time of harvest. The stem stereotype is that green stems are less suited for winemaking (and lead to green tannins and aromas), and lignified stems are what is desired, offering the most mature tannins and minimal green character. In researching this article, and personally as a winemaker, I’ve yet to come across much evidence that stems are ever very lignified.A quick (and simplified) note on plant morphology will be useful here. What we refer to as a stem has a few different parts. To discuss lignification, we only need to distinguish between the rachis and peduncle. The rachis is the branched part of the stem, eventually leading to grapes; it is the vast majority of the structure. The rachis is attached to the cane by a short stalk called a peduncle.

For David Croix, “to be honest, in Burgundy, I very rarely see lignified stems. The peduncle gets lignified in some years, but it almost never goes further than this.”

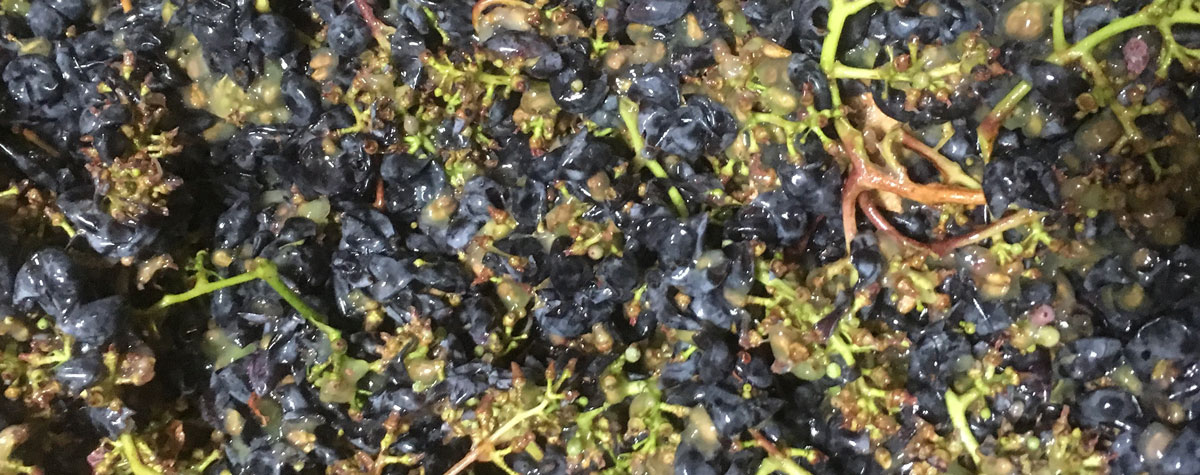

The Pinot Noir grapes above came in at 14.2% potential alcohol, but there is only a little peduncle lignification.

Dylan Grigg (above) of Meristem Viticulture in the Adelaide Hills, South Australia, who has a PhD in viticulture science, says: “Sure lignification creeps down the peduncle a bit depending on the variety, it makes for a useful ampelography tool and can influence harvest effort, but I’m not sold on lignification representing superior quality or maturity level.”

Regarding varietal differences, he notes: “Mourvèdre (above) and Graciano often have woody stalks compared to Shiraz.” Dylan also makes a good evolutionary point which may explain why in reality stems may only slightly lignify: “What’s the advantage of the vine to expend energy to lignify a structure that is temporary, merely a carrier for one season’s fruit and seeds?”

He contrasts this with tendrils, which are identical in early development to the rachis and thus initially the same plant organ, each taking different developmental paths after a certain point. Tendrils do fully lignify and have an advantage from doing so. “Once [a tendril] has attached to an object for support, this remains over many seasons so shoots can survive over winter.” Thus the energy the plant spends to lignify a tendril is justified, whereas doing so for a cluster would be a waste.

Early pickers may rarely see any peduncle browning. On the degree of lignification he sees in South Australia, Taras Ochota of Ochota Barrels says: “It depends on the variety, but not very lignified ever, as I pick pretty early in general so as to capture natural acidity.”

There may be differences between totally green stems and those with a lignified portion of the peduncle, but overall, the idea of especially mature or fully lignified stems does appear to be an urban (or in our case rural) legend.

Stem aromas

Although the main aroma descriptors one hears for stem fermented wines are usually green or stemmy, which are attributable to their methoxypyrazine content (1) and often spice or floral, in researching this article, I came across a wide array of winemaker’s descriptions: mulch, soy sauce, rose, mint, black tea, and eucalyptus.Methoxypyrazines are no surprise – that a green piece of plant would lead to green aromas makes sense – but what is it in stems that leads to floral, spice and the other aromatics people feel result from stem use?

Unfortunately, little or no research has been done on this. A couple of researchers I spoke with speculated on what might be going on: “It may be... that stems facilitate formation of fruity smelling thiols,” thought Dr Gavin Sacks, a professor of Food Science at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Thiols are a class of aroma compounds common in grapes (think passion fruit, currants, grapefruit, guava), which can have a sensory impact at extremely low concentrations relative to other aroma compounds. They’re found in grapes such as Riesling, Semillion, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, but reach their most obvious and extreme expression in Sauvignon Blanc (2).

'Stems produce high concentrations of C6 compounds when they are crushed'Dr Sacks continued: “Grapes can produce varietal thiol precursors following crushing by reaction of C6 compounds with glutathione (3). A free thiol can later be released by yeast during fermentation. Stems produce high concentrations of C6 compounds when they are crushed, so you could end up with higher precursor concentrations, and thus higher thiol concentrations if you add stems to a ferment.”

Stem fermented wines are also noted for being less overtly fruity. While the herbaceous addition of methoxypyrazines may counterbalance grapes’ inherent fruit character, the increase in tannins is also a factor. Dr Bruce Zoecklein, a professor at Virginia Tech University in Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, points out that stems can “impact the aromatic profile directly or indirectly. The direct impact is to lower the perception of fruit (generally, more phenols means lower fruit perception). The indirect impact is the result of the matrix effect, [where certain compounds] impact the volatility of a number of [other aromatic] compounds.” Additionally, Dr Zoecklein feels that “there are likely a host of compounds derived from stems that could impact the aromatic profile.”

A little speculation of my own here, furthering this line of thought: there are numerous aromatic compounds (certain esters, monoterpenes and norisoprenoids and surely others) which not only impact the intensity of other aroma compounds in a wine, but can change the way other compounds smell. Even more mindbending is that certain aroma compounds, when at or near sensory threshold levels, can cause aromas in a wine that neither the compound itself nor any compound in the wine actually smell like. In other words, wine aroma can be affected in a myriad of strange and indirect ways, even from tiny amounts of a compound. It would not be surprising if compounds released from stems could lead to similar effects.

Where stem inclusion leads to a portion of uncrushed berries that undergo a semicarbonic maceration, higher concentrations of fruity smelling esters will be produced. However, as esters, most of these will breakdown over the first year of a wine’s life and cease to have an impact. These also do not come from the stems themselves, but may result from whole cluster fermentations.

Conclusion

It’s clear that stems are a complex and highly variable aspect of winemaking. With so many variables affecting their impact, there’s no shortcut to a refined formula for their use. They are also a subject with many more nuts for researchers to crack before we can claim a comprehensive understanding of their effects and potential.California-based Alex Russan is the owner-winemaker of Metrick Wines. He also has a Spanish wine import company and Sherry label, Alexander Jules.

.png)