Researchers in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, have compared the vine performances and the costs of different degrees of mechanisation over a five-year period (2011–2015). The three pruning treatments they compared were:

- Manual pruning (MAN) – retaining spurs with 3-4 count nodes and some shorter spurs to avoid the depletion of the permanent cordon;

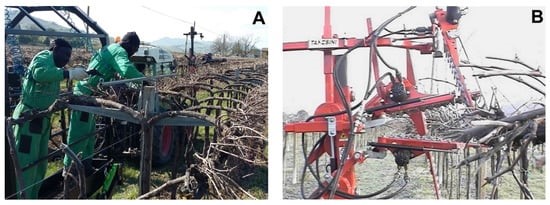

- Mechanical pre-pruning and simultaneous manual follow-up (MP+F). The mechanical pre-pruning was performed by a four-cutter bars unit applied close to the curtain to leave about 3-4 count nodes per spur and a simultaneous manual follow-up conducted by two operators with pneumatic shears from a tractor-drawn platform to thin out the machine-pruned wood (see photo A below);

- Mechanical pruning without a manual follow-up (MP) (see photo B below).

One thing I like about this research is these pruning treatments started in 2005 and were repeated on the same vines every year before the beginning of the experiment, so the vines were already used to the pruning method when the experiment started.

What did they find?

Bear in mind, these are the results of trials on Trebbiano Romagnolo, a high-yielding variety with low basal bud fruitfulness that’s widely cultivated in the oriental area of Emilia-Romagna.

The three-year mean of the count nodes per vine increased in the MP+F by about 57% compared to MAN, while it more than doubled in the MP. Similarly, the spurs per vine in the MP increased drastically compared to MAN, while the increase of the MP+F was less intense. On the other hand, the mechanical pruning treatments reduced the number of count nodes per spur. Considering that mechanical pruning did not affect the budbreak (around 80% in all the treatments), the number of shoots followed the same trend as that of the nodes. The number of clusters was also higher in the MP compared to MAN, but in this case, the increase was limited to 38% since the shoot fertility level was almost halved by the MP. The MP+F reached an intermediate level compared to the other treatments.

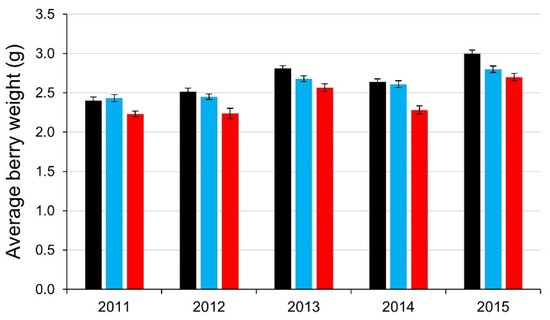

No significant differences were found concerning cluster compactness and the incidence of cluster rot, but the mechanical pruning treatments increased the yield per vine (as expected), and the estimated crop level was higher than 19 t/ha in the MP+F and MP, while MAN reached 17 t/ha. Conversely, the cluster weight was reduced by about 10% and 25% in the MP+F and MP, respectively. Also, the berry weight decreased significantly with the increase of the node number, but a significant pruning x year interaction occurred. The berry weight was notably lower for the MP compared to MAN for the five years, while the MP+F was about the same level as MAN in 2011, 2012, and 2014 and lower in 2013 and 2015 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Interactive effect of treatments and year on berry weight of Trebbiano Romagnolo vines subjected to different pruning treatments. MAN, manual pruning (black bar); MP+F, mechanical pre-pruning and simultaneous manual follow up (blue); MP, mechanical pruning (red). Data recorded over 2011–2015.

Soluble solids did not differ between the pruning treatments, while titratable acidity was slightly higher in the MP berries. The higher titratable acidity of the MP berries might be due to the higher number of shoots that shaded more intensely the clusters, reducing the degradation of malic acid.

Although in the MP vines the number of shoots was the highest, the weight of the pruning wood recorded in the winter of the last year of the experiment was the lowest, indicating that those shoots were thinner and lighter than those of the other treatments. This suggests that the mechanically pruned vines' shoots contained fewer reserves for the following year, partially explaining the reduction of the shoot fruitfulness and cluster weight.

It’s interesting that the strong increase in the node number of MP led to a limited increase in productivity. Does this mean the vines self-regulate?

Yes, this study found that mechanically pruned vines are subjected to self-regulation mechanisms that downregulate the budbreak percentage, shoot fruitfulness, and, to a lesser extent, cluster weight, reaching an appreciable balance of the crop load to grape composition, despite being characterised by a higher bud load than vines pruned manually. But it depends on the variety. The yield compensation is more effective in varieties characterised by low-to-medium basal bud fruitfulness rather than highly fruitful basal buds, which might result in overcropping.

Whether the pruning is mechanised or manual, do we know the ideal number of count nodes to leave on a balanced vine?

Research in New Zealand, conducted in three commercial vineyard blocks of Sauvignon Blanc (two in Awatere Valley, Marlborough, and the other in Waipara, Canterbury), confirmed that:

- Grapevines respond to low node loads by producing more shoots than the total number of retained nodes on canes and spurs, resulting in a vine budburst of 100% or higher.

- Retaining fewer nodes incentivises the development of more than one primordial bud per node, resulting not only in budburst on all count nodes (nodes intentionally retained as future growing points), but also, in some instances, in double-shoots or multiple shoots arising from a single node. These extra shoots are referred to as non-count shoots. Additional non-count shoots also arise from quiescent buds within the head of the vine, or on the trunk.

- Retaining excessive node numbers generally leads to fewer shoots than the total number of retained nodes (less than 100% budburst) and greater numbers of blind nodes (also termed ‘blind buds’). For example, in another study a vine budburst of 115-120% was reported on Sauvignon Blanc grapevines cane-pruned to 24 nodes compared with 85-92% on 72-node vines. Likewise, reducing the retained node number from 50 to 30 nodes increased the budburst in another study of Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir and Sauvignon by approximately 5%.

- Three-node spurs developed more blind nodes than one-node and two-node spurs.

- Budburst along the canes and spurs started at the most distal node.

How much quicker is a machine compared to a man?

During the mechanical pruning research in Italy, to obtain a regular and accurate cut, a maximum cutting bar frequency was set (90 cuts/min) while keeping a limited forward speed of the tractor. For the MP, the average mean speed adopted during the five years of the trial was 1.5 km/h, while for the mechanical pruning followed by hand-finishing, the machinery speed was reduced to 1.2 km/h to allow the hand-pruners to remove overlapped spurs and those growing towards the inside of the trellis structure. Under these conditions, the first worker operated 45 cuts per minute, while the second one, engaged in a more careful selection of the spurs to be eliminated, was able to keep a mean of 35 cuts per minute. In MAN, the pruners maintained a speed of 66 m/h, with an average frequency of 25 cuts per minute.

The mean speeds were:

MP – 3.70 h/ha

MP+F (with three operators) – 4.55 h/ha

MAN – 75.8 h/ha

The report states: “Comparing the worker hours saved (which included the working time of the driver), the two mechanised pruning treatments made it possible to reduce the worker time employed by 82% and 91%, respectively, for the MP+F and MP compared to MAN.”

What about the costs comparison?

Generally, the researchers reckon hand-pruning accounts for up to 75% of the yearly labour demand, and such high labour can be lowered through mechanisation by 50 to 90%, depending on the training system used and the extent of hand clean-up. The MP treatment was the most economically convenient, with a vineyard surface above 1.5ha. Mechanical pruning with manual finishing became a better strategy than manual pruning when the vineyard surface was greater than 2.9ha.

The operating cost of hand-pruning a 5ha vineyard, the report says, is €1,137 per ha. With MP+F you would save €326 per ha and with MP you would save €664/ha. For a 30ha vineyard, the savings are 61% and 80%, corresponding to €693/ha for MP+F and €908/ha for MP.

What is their conclusion?

The researchers said: “The agronomic and economic results obtained in this five-year study… confirm that mechanical pruning may be profitably applied also on grapevine varieties characterised by low basal bud fruitfulness, such as Trebbiano Romagnolo. Our data indicate that even with a dramatic increase in the node number, the yield compensation factors limited the increase of productivity to less than 15%, allowing the harvest of grapes with a similar composition as that of manual pruning… The data reported in this research indicate that also mechanical pruning without any manual follow-up is feasible on Trebbiano Romagnolo and that the vine performances are very similar to those of the vines subjected to a light manual follow-up. Moreover, our results demonstrated that economic sustainability might also be achieved in vineyards of about three hectares.”

.png)