Quinta do Vallado’s top field blend, Adelaide, comes from a vineyard further west, in Rio Torto, where the climate is a little cooler and rainier. This vineyard, planted mostly in the 1940s, features more than 30 grape varieties.

Both wines are made in subtly different ways. The differences are intriguing. And surprising – because the estates, otherwise, have so much in common.

Both are historic estates. Both belong to Portuguese families – an increasing rarity among large estates in the Douro region. Both made their names through the production of port. Both have followed the trend in the Douro over the past 20 years to make dry wines from the native port varieties. So much so, dry wines now account for about 90% of their output.

Both are successfully using wine tourism to promote their brands. In fact, both have fantastic wine tourism offers and plan to increase the number of rooms available for overnight stays.

Quinta do Crasto (above), owned by Leonor and Jorge Roquette, has been in the World’s Best Vineyards Top 50 since the list’s inception three years ago, slipping from a high of no4 in 2019 to this year’s no16. But it’s still the highest-ranking vineyard in Portugal.

‘We want to become the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti of Portugal’Situated on the right bank of the Douro River between Régua and Pinhão, Quinta do Crasto currently offers four guest suites. But it plans to build a new boutique hotel, with 12-15 rooms, in the century-old manor house, currently home to fourth-generation custodians Leonor and Jorge. “The projects are currently being finalised and we expect to start the work in the beginning of 2022,” son Miguel Roquette tells me. “We expect to have it ready by summer 2023.”

The hotel will be high-end, like the wines – in keeping with the family’s goal of rivalling the best in the world. “We want to become the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti of Portugal,” Miguel says matter-of-factly. “It’s very clear. It seems arrogant, but we are working in every sense of the way to achieve this stature. We’re not there yet, we’re still scratching. I think we are at 60-65% of our potential.”

Quinta do Crasto’s famous trapezoid infinity pool, cut high up into the Douro hillside and overlooking the river, will receive an upgrade next year, too. Bathrooms and changing rooms are to be added underneath the pool. There will also be a lounge and spaces for further relaxation, and firepits.

“The concept for the hotel is exactly the same as the swimming pool,” Miguel says. “We want guests to wake up in the morning, to turn the shutters up, and as the shutters open up you are going to see your feet and after that you are going to see the Douro river. Infinity in every single room. That’s the concept.”

Quinta do Vallado is a new entry in this year’s list. In at no49, it already has two first-class boutique hotels near the river: the Quinta do Vallado wine hotel in Régua and the Casa do Rio in Foz Côa. At Quinta do Vallado there are five suites set amid the traditional splendour of the 18th-century manor house, the ochre-washed exterior of which is reflected on the wines’ vibrant labels. By contrast, the striking stony edifice of the newer wing (above), built in 2012 by Francisco Vieira de Campos using the local schist, contains eight rooms with a sleek, moody and modern feel.

Work will begin soon on adding new rooms, increasing Quinta do Vallado’s total to 20.

Quinta do Vallado (first mentioned in a document in 1716) is still run by the descendants of the legendary Dona Antónia Adeleide Ferreira: the two cousins João Ferreira Álvares Ribeiro and Francisco Ferreira, with winemaking consultancy from another cousin, Francisco Olazabal of Quinta do Vale Meão. Winemakers Francisco Ferreira (right) and Francisco Olazabal are pictured above.

Francisco Ferreira tells me wine tourism is “a fantastic way” to promote the wines, adding: “It’s a good way to gain money but more than this, it’s the better way to promote the region, our brand and our wines.”

What’s been encouraging for both producers is that they have had good occupancy rates during the pandemic – with Portuguese visitors discovering the region. Global trends are also in their favour. Gastronomy, wines, and nature are tipped to be a winning combination heading back to ‘normality’.

Flagship field blends

Having been sidetracked by their wine tourism developments, I return to my main topic: the wine estates’ flagship field blends. Making ports from field blends is part of their DNA, but making dry wines from the same vineyards is a recent development, so I wanted to know whether they use modern or traditional winemaking techniques for Quinta do Crasto’s Vinha Maria Teresa and Quinta do Vallado’s Adelaide, and how much difference there is between the winemaking techniques employed by these historic wineries.Vinha Maria Teresa

When Leonor and Jorge took over in 1981, Quinta do Crasto was focused on port production. Now it’s only 10% of their annual output.Since 1994, they have revitalised and extended the vineyards to produce an additional selection of dry red and white wines focusing on native grape varieties. The two most special cuvées, Vinha Maria Teresa and Vinha da Ponte, are red blends from old vines. They are only made in the best years, and the grapes are foot-stomped in a lagar. These lagares have recently been renovated.

The first dry Vinha Maria Teresa, from a vineyard usually used for port, came in 1998. Even that year, the intention was to make a port but, according to fifth-generation Miguel, “after four or five hours in the lagar, we decided to stop and make a dry wine”. The decision of whether the grapes from this vineyard are destined for a port or dry wine – or both – is still, sometimes, made on the spot.

In recent years, Quinta do Crasto has carried out a genetic study of the vines in the Maria Teresa vineyard to protect its identity. The tendency in such old vineyards, replanted after phylloxera devasted the region, is to replace dead vines with Touriga Nacional. “It’s the safest way to go but if you keep doing this for the next few years, you’re going to lose the identity. So, what we wanted to do is to find out what we had,” Miguel states.

The research showed they had 54 different varieties. “It’s a fruit salad,” Miguel admits. But it produces a red wine with great ageing potential, refreshing acidity, and prominent fruit flavours – everything you want from a high-end Douro red. But the volume is tiny as each plant on average produces a mere 150g of fruit.

The winemaking team, led by Manuel Lobo and Tomás Roquette, admits dry winemaking in the Douro is “still a learning process” as they have so many different varieties, soils, exposure, and altitudes to consider – as well as optimum picking time, time in press, the type of fermentation, the length of macerations, the type of oak, the time in oak… for field blends, blends and varietals.

The focus for the past two decades has been getting the raw material in the best possible shape. “Without good fruit you don’t make miracles,” Miguel points out.

Subtle changes have made a significant difference. At the Maria Teresa vineyard, the tradition was to pick this small parcel on one specific day. But, since the 2011 vintage, the harvest is spread over four days – selecting from different parts, with different aspects and soils, and vinifying these separately. It’s led to a wine that gets very high scores (97-98 points) and gains the winery great exposure, even though production is very limited.

The other significant change is the time in oak and the type of oak. They are currently using 14 different coopers (90% French oak, 10% American oak).

‘I think in the next five to ten years, Douro wines will be at the very top’

The winemaking

- The grapes are taken to the winery in 22kg boxes.

- On arrival, they are rigorously inspected on a sorting table. The grapes are then completely destemmed and crushed in the lagares with four hours of foot-stomping. “It’s a very gentle process,” Miguel says.

- After this, the juice is transferred to temperature-controlled stainless-steel tanks for regular pump-overs and “careful extraction to retain the tannins”.

- Once the alcoholic fermentation is complete, the wine is gently pressed.

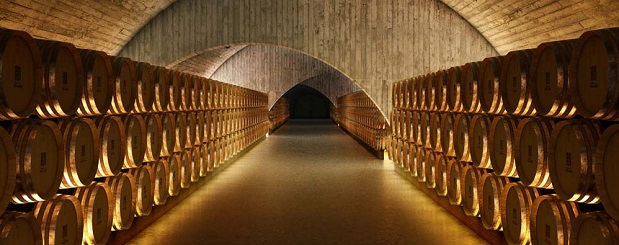

- The wine ages for about 20 months in new oak barrels (90% French oak, 10% American oak) with silicon bungs.

- The casks are placed on an OXOline barrel management system (below), where the barrels can be rolled to stir the lees. Miguel says this system has two advantages – it’s less oxidative than batonnage and it’s a more efficient method of mixing the lees. “When you rotate three times, the entire yeast is in contact with the wine,” he states.

- The final wine is made from a selection of the finest barrels.

“The first thing you have to get is fruit; the oak has to be there playing its role as a base underneath. What you need is to get the typical Douro fruit, the dark berries, the wildflowers of the Douro vegetation. If the first thing you get is oak, that’s a bad sign.

“We love fruit. We think wine is all about fruit. The fruit in the Douro is extremely complex when it comes to old vines and you start seeing the different layers and how the wine opens up and talks to you.”

Miguel adds: “I think in the next five to ten years, Douro wines will be at the very top. You will talk about Douro for dry wines as you talk about Burgundy and Bordeaux without any doubt.

“There’s a lot to explore still but Douro is going on the right track and you will see port producers, they have no choice, they have to start looking into dry wines in a serious way.”

Adelaide

Quinta do Vallada, which has been producing dry wines since 1993, has doubled the price of its old-vine signature red, Adelaide. In recent years the price has gone from €100 to €200. Francisco Ferreira admits this is “huge for a Portuguese wine”.But he also confesses “it’s a huge success”.

Part of the reason for the price hike is that the wine spends longer ageing. It used to be released after two years, now it’s more likely to be five or six. The 2019 has only recently been bottled. They will taste it regularly to see how it develops. The 2014 was released in 2019, and the 2015 is the new release for 2021.

“We thought, this is our top-quality wine, we must release it when we think it’s really ready. Unfortunately,” he says, “in Douro, we used to release the wines too early.”

The other reason for the price increase is that this wine has been selling out in two or three months.

The more expensive version does, however, now come in a beautiful box.

Like Vinha Maria Teresa, Adelaide is a limited-edition wine (about 4,000 bottles) that’s only bottled in exceptional years to maintain its reputation.

The unusual name for a Portuguese wine is a tribute to the family’s ancestor, Dona Antónia Adelaide Ferreira, who was instrumental in formulating many of the techniques now used in Portuguese winemaking.

Francisco, great-great-great grandson of Dona, tells me that of the 120ha under the family’s control, 22ha are rented, including the old vines that produce Adelaide.

Planted close together (at a density of 7,000 vines per hectare) on poor schist soils, “production per plant is very low”. Yield on average is 400g per plant, equivalent to 2.8 tons per hectare.

“When the varieties are good, these old vineyards produce wines with lots of concentration, lots of structure, lots of complexity, but at the same time what is fantastic for me – two things, first the balance between the high alcohol and acidity, and second, the quality of the tannins.”

The winemaking

They used to pick the grapes over four days and vinify them in the same way but Francisco discovered “a part of this 10ha of old vines usually produces wines very dry, very aggressive, with too much tannin and bitterness – and not so much fruit”. Every couple of years he found himself demoting this portion to the reserve field blend or basic red wine.But, after studying the different parcels, they found there was a larger proportion of Tinta Roriz (Tempranillo) and Tinta Barroca in the parcel with northwest exposition. So, they vinified this portion differently:

- Picking earlier – at 13% potential alcohol instead of the usual 14-14.5%.

- Only destemming and crushing about 50% of the grapes. 50% goes into stainless-steel vats with stems and without crushing for carbonic maceration. The remaining 50% is crushed and destemmed before going into stainless-steel vats for a 14-day fermentation.

- Using 50% of the stems seems a somewhat surprising move since they are trying to avoid aggressive tannins. But instead of the usual 3-5 pump-overs per day, they do it once for one minute. “So it’s a very, very low extraction,” Francisco says. “The stems give some tannins that the skins will not give and also some freshness and vibrancy.”

For Francisco, the Douro is about complexity and diversity. They illustrate this by releasing three very different wines from their small portfolio of old vines. From the parcel with the southwest exposition, they make Vinha da Granja “with more concentrated fruit, lots of colour and freshness”.

The typical vinification for Adelaide is:

- Collect the grapes in 20kg plastic crates;

- Sort on a belt;

- Destem and crush;

- Ferment in stainless-steel tanks with a capacity of 4-5 tons;

- Inoculate with Bordeaux yeast to reduce the risk of oxidation, although once the harvest has started and “the yeast is in the air” there is less need to inoculate the later-picked grapes;

- Fermentation at 24-26°C (down from the previous 26-28°C), with Tinta Roriz even lower at 22-23°C for “less extraction”;

- A slow, soft extraction “to take all the potential of the grapes and make the wine you intend to make”;

- Robotic remontage for the first few days of the fermentation – 3-4 extractions per day for 5 minutes, then reduced to 2-3 pump-overs per day (for 2 minutes) until the fermentation finishes;

- After fermentation and pressing, the grapes go into 225L new French oak barrels (mainly from Tarannsaud) for MLF and 20 months’ ageing.

However, they have been so pleased with the quality and success of their field blends that they have resumed planting mixed vineyards. Typically using 15 of the most appropriate varieties, planted at 7,000 plants per hectare to create “big competition between plants”.

It’s a trend I applaud. I’m also pleased there will be plenty of choice of places to stay when I resume my travels and try these field blends in situ – with views of the steep, terraced vineyards and the glimmering Douro below.

.png)