d’Arenberg’s chief winemaker, Chester Osborn, is as complex as his wines, as colourful as his shirts, and as creative as the five-storey ‘Rubik’s Cube’ in the middle of the family vineyards.

I met up with the Australian legend to discuss one of his signature wines, The Dead Arm Shiraz. While the rest of the wine world worries about vine diseases, he celebrates Eutypa Lata with this wine.

Vines affected by the fungus Eutypa Lata are usually severely pruned or replanted, as one half – or an ‘arm’ – of the vine slowly dies. But while that side becomes lifeless and brittle, all of the energy goes into the small crop on the other side. Chester says these grapes display amazing intensity: “Less stress, more of the terroir, more earth and complex characters.”

d’Arenberg’s The Dead Arm Shiraz is one of McLaren Vale’s iconic wines. While it shows the power and concentration associated with the region’s Shiraz wines, it also has an elegance and refinement that few others from the region possess.

The techniques behind this wine

Chester walks the rows of dry-grown vines, tasting the grapes to determine the ideal picking time.About 40% of the grapes come from vines that are 100 to 129 years old – some planted by his great-grandfather. 50% or so are from 50-year-old vines, and 10% are from vines 25 years old, which add “freshness and spiciness”.

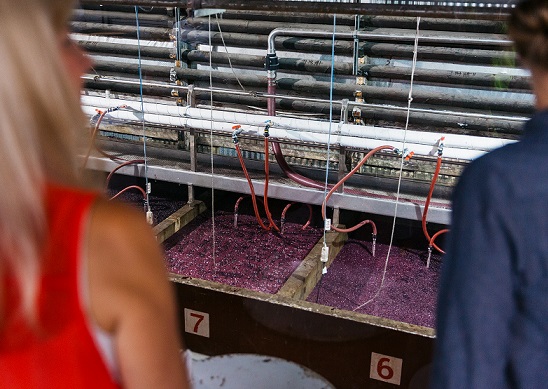

He brings them in at 16-18°C. Small batches are crushed in the Demoisy open-mouthed, rubber toothed crusher and then transferred to five-tonne open fermenters, which can be moved around with a forklift. They are stainless steel but are based on the design of the original concrete fermenters that his father, Francis d’Arenberg Osborn, used. They have 250 of these, so they can process 1,000 tonnes of grape at a time.

A small amount of yeast is added “to get it ticking” (and maybe some more at day 3). Chester inoculates most of his wines because the yeasts on the grapes are weak, as he hasn’t fertilised the vineyards for 20 years.

The low-yielding ‘dead arm’ vines also produce grapes with high acidity, high alcohol potential (14-14.5%), high tannins, and low nitrogen. “It’s a recipe for difficult fermentations,” he points out.

He lets the temperature of the ferment rise and when it reaches 30°C about halfway through (at 7% alcohol) he chills it down “to slow it all down”.

About two-thirds of the way through fermentation, he drains off half the juice and gets his cellarhands to foot-stomp the skins in fishing waders to mix up the cool juice and warm skins. “That’s basically so the skins are not too warm for the end of ferment,” he tells me. “That would give a richer, blowsier character and lose a bit of finesse and minerality, and the potassium extraction is higher which upsets the acid – it’s not as pure.

“Then we put it all back together.”

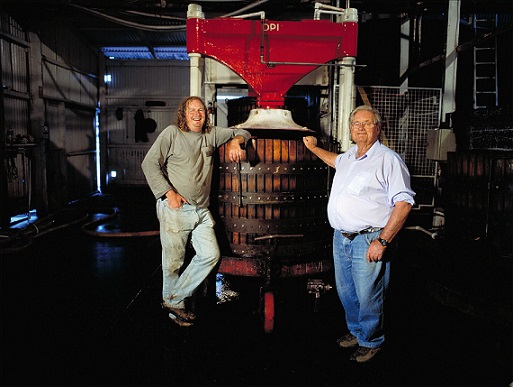

When he feels the tannin extraction is just right, the wine is basket-pressed. He has 10 two-tonne basket presses like the one above (photo shows Chester with his father, Francis d’Arenberg Osborn).

Each batch – kept separate until final blending – is then transferred to a mixture of new and used French barriques to complete the fermentation and malolactic conversion.

The wines are aged on lees for about 20 months to keep the wine fresh while also reducing the oak influence.

There is no racking until final blending.

Chester, senior winemaker Jack Walton, and the rest of the winemaking team undertake an extensive barrel tasting process to determine the final blend, which is bottled without fining or filtering.

“We still use all the old-fashioned equipment the same way my great-grandfather did when he built the winery in 1927,” Chester says. “So tiny fermenters, no plunging, no pumping over, foot trodden once during the fermentation, basket-pressed, French oak for about 20 months with no racking, no filtering.”

I confess to Chester that it’s hard to imagine such old-fashioned techniques in a business with such a modern building and wine tourism offer (no29 in the World’s Best Vineyard list). Chester explains there’s modern thinking behind the winemaking: “Although it’s traditional style, there’s a lot of modern understanding that goes into it. The equipment’s all fine, it still all works very well. I’ve changed things in a sense – understanding the yeasts and which ones can be naturally fermented, really watching them through the ferment and understanding which temperature regimes are required for different lots and different years, tasting through ferments more religiously, pressing them when they’re nearly finished.

“There’s also a lot more understanding in types of oak, using very low toasted oak – lower than low toast – so I don’t get any caramel or any smoky character, I just get a nice sweet fruit, sappy-like character which is quite long and fine. And because our wines are all about length and grittiness and fragrance then they help to nullify each other and carry each other.”

Fourth-generation winemaker Chester, who had helped out in the vineyards and cellar from the age of seven, became the chief winemaker in 1984, when he was 22.

He says he’s been learning on the job ever since.

“The biggest thing is to train your palate,” he says. “If you can taste and you can watch what you’re doing, and you can work out that flavour came from that thing you did there, then you know exactly what is going on and you can adapt everything. Eventually you get to know where all the flavours of the wine are coming from – the given season, whether there was wind or rain, what effect a few leaves missing had. All of those things have an impact on the flavour and you can see it in the wine.”

The estate now sells between 200,000 and 300,000 9L cases a year from just over 200ha of vines (about half of which belong to the family) and the building he’d thought about for 12 years before he got his family to agree to spend millions on it now draws up to 1,500 people a day on weekends.

There, visitors can try wines such as The Cenosilicaphobic Cat (named after the fear of an empty glass) and The Athazagoraphobic Cat. ‘Athazagoraphobic’ means fear of being forgotten. There’s no chance of that for Chester, his Dead Arm Shiraz or the d’Arenberg Cube.

Canopy's Australian winemaker series

Part 1: Innovative winemaker Steve James talks clones, tulip-shaped fermenters, using a machine-harvester to control botrytis, Chenin Blanc fizz and weevils…Next issue: Bruce Tyrell. Sign up here to make sure you don't miss it.

.png)