As August 2025 began, the South African wine industry faced a 30% U.S. tariff that took effect immediately. This blow threatens South Africa's competitiveness in the American market, where its wines have gained popularity among quality-conscious consumers.

Yet many winemakers remain defiantly optimistic, seeing this as a necessary push for change. Rather than a sudden disaster, these tariffs are accelerating a transformation that has been unfolding over three decades. South Africa's wine industry evolved from a cooperative-dominated, volume-driven sector emerging from the shadows of apartheid into a nimble, innovative powerhouse poised for global premium status. This is not an overnight reinvention, but a gradual, determined effort to turn challenges into opportunities.

A legacy of reinvention

The roots trace back to 1991, when the lifting of international sanctions — following Nelson Mandela's release — opened the floodgates for South African wine. Prior to 1994 democracy, the industry was shackled by apartheid-era isolation and heavy regulation through the Koöperatieve Wijnbouwers Vereniging (KWV), a powerful cooperative established in 1918 that controlled production, prices, and exports. Independent wineries struggled under a system favouring bulk production for cooperatives, which accounted for over 60% of 1980s output.

The post-1994 "rainbow nation" era generated global curiosity, initially boosting exports. However, structural flaws emerged. Winemakers were stretched thin. Young graduates found themselves in senior roles without international experience and seasoned professionals came from cooperative backgrounds focused on high-volume, technically correct production rather than the finesse that evolving global tastes demanded. South Africa lacked brand juggernauts like Concha y Toro, Penfolds, or Gallo. While KWV and Distell dominated domestically — with Nederburg achieving notable scale — smaller brands like Meerlust, Simonsig, Kanonkop, and Rustenberg remained capable but limited in scalability.

Without strong brand anchors, South African wines competed primarily on price rather than prestige. Low domestic willingness to pay premiums resulted in slim margins, fuelling a cycle where exports undercut themselves for shelf space. Compounding this was absent government support. While Australia and Chile leveraged state backing to build million-case brands like Yellow Tail or Jacob's Creek — dominating supermarkets where 70-80% of global wine sales occur — South Africa relied on self-funded initiatives through Wines of South Africa (WOSA), targeting one market at a time as rivals flooded shelves with laddered portfolios. The result was a "cheap and cheerful" perception that trapped the industry in low-margin decades.

The tide turned in the late 2000s through a quiet revolution led by independent winemakers. A new generation, free from legacy infrastructure constraints, established virtual wineries —sourcing grapes without owning vineyards. This nimbleness frustrated established cooperatives but injected sector vitality.

These upstarts shifted from imitation to authenticity: why ape Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc or Barossa Shiraz when the Cape boasted unique treasures? Old-vine Chenin Blanc yields wines rivalling the Loire's best in complexity and ageability. Swartland's Mediterranean blends expressed raw, terroir-driven soul. Pinotage, long derided as rustic, found elegance, becoming South Africa's equivalent of Carmenère or Zinfandel — a proprietary USP.

A sense of place

Meanwhile, regional identity emerged as the linchpin. Smaller regions, freer from historical burdens, emerged with their signature grapes and styles. Swartland pioneered with its revolutionary charter, safeguarding old bush vines and traditional practices. Robertson's limestone soils have become a magnet for sparkling wine, particularly in Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Hemel-en-Aarde pioneered cooler areas for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, while Elgin's high plateau — once known for apple production — carved a cool-climate niche, offering tension and minerality as Burgundy warms. Durbanville delivered refined, mineral Sauvignon Blanc; Elim countered with herbaceous intensity.

Traditional areas like Paarl and Stellenbosch gained traction after years of identity diffusion. Previously amorphous, Stellenbosch has identified sub-regions that have helped define its territory and signature grapes that, over time, will attract higher prices. They embraced Cabernet Sauvignon and blends, leveraging diverse mesoclimates to produce cassis-laced, cedar-infused expressions, while also producing benchmark Shiraz and housing the country's oldest Chenin vines. This wasn't superficial branding, but one that mirrored successes overseas — Clare Valley Riesling, Central Otago Pinot Noir — fostering specialisation over hedging.

Paradoxically, lacking corporate giants became strength. Without behemoths dictating styles, innovation flourished. Family operations and virtual setups lowered barriers, enabling experimentation with heritage varieties such as Pinotage and Chenin Blanc and overlooked grapes — Colombard, Clairette Blanche, Hanepoort and Tinta Baroccav — alongside winemaking techniques from stem inclusion and spontaneous fermentation to vessels like foudre and concrete. International buy-ins diversified ownership, but the ecosystem remains accessible, fostering what many call the world's most dynamic wine scene.

By the 2010s, vintages such as 2015, 2017, and 2021 demonstrated the ageability of South African wines, capturing the attention of collectors and investors. The 2025 harvest may join those ranks. The Cape Winemakers Guild innovated its auction offerings while Strauss & Co. and Wine Cellar built secondary markets, shifting perceptions from everyday quaffers to cellar-worthy assets.

Today's crises — tariffs, economic fragility, climate shifts — are catalysing momentum. The 30% U.S. duty compounds declining sales and low consumer confidence, while proposed excise tax hikes squeeze thin margins. Infrastructure woes, such as Eskom's electricity crisis and demographic challenges — engaging millennials and Gen Z (66% of South Africans under 35), who view wine as outdated — add complexity. Transformation remains thorny: empowering black winemakers faces land capitalisation hurdles.

Yet opportunities abound. Tariffs could inadvertently solve the pricing paradox, forcing wines into higher tiers and shedding the "cheap" stigma. Premiumisation shifts emphasis from volume to value through vineyard renewal and quality focus as highlighted in the BFAP 2025 baseline. Climate change may be advantageous to the Cape, as diverse microclimates and the Benguela current provide a certain resilience, especially for areas closer to the coast.

South Africans are resilient, having faced these challenges before. South Africa's wine renaissance isn't born of crisis but refined by it — a three-decade saga of small producers championing distinctiveness over duplication. With ancient soils, old vines, and innovative spirits, the Cape isn't just surviving; it's redefining what New World wine can be.

Constraints and Creativity: How Crisis Drives Quality in South African Wine

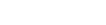

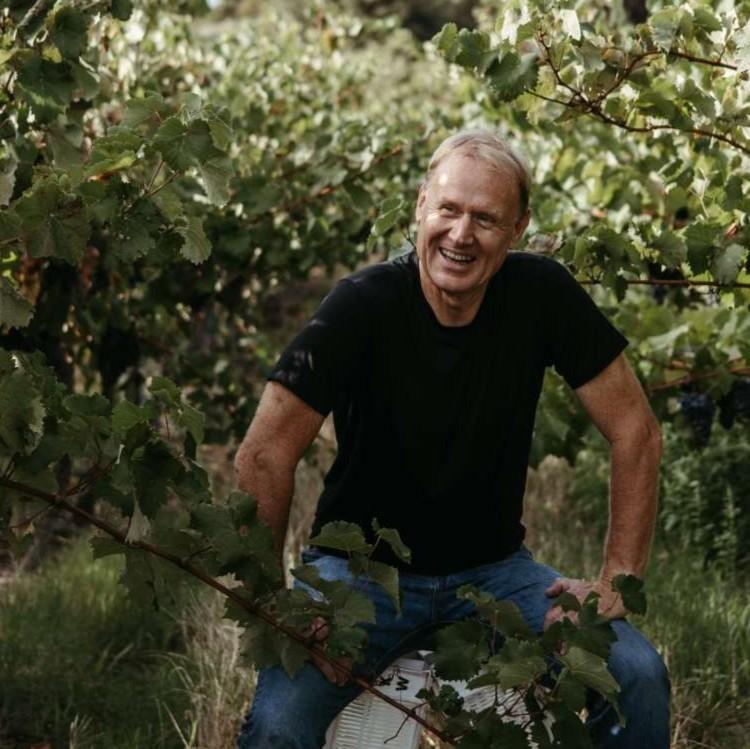

As a 30% US tariff hits South African wine exports, the Cape's producers face another defining moment. Yet there is renewal in adversity, says Richard Kershaw MW.

Credit: Oak Valley Estate in Elgin

.png)