What does the latest vineyard research tell us?

‘We are approaching a tipping point’Warming temperatures over the past 60 years have led to increased wine quality, but a new study looking at sugar and colour content in grapes indicates there may be big trouble ahead. The research – a collaborative effort by the University of California, Davis, and University of Bordeaux – looked at the relationships between global warming, fruit ripening, and wine quality over six decades in the renowned red wine regions of Napa Valley and Bordeaux, and then confirmed the findings with a five-year trial in Napa.

The study shows that both regions have warmed substantially since the 1980s and that, until now, this warming has contributed to increases in the average wine quality. However, ripening relationships revealed that we are reaching a plateau and raise concerns that we may be approaching a tipping point in traditional wine-growing regions.

Some of the findings:

- Temperatures increased significantly in Napa and Bordeaux between 1950 and 2020, and especially since the early 1980s.

- There have been no apparent long-term changes in precipitation in the regions, although in Bordeaux increasing maximum growing season temperature is weakly correlated with decreasing precipitation.

- The speed of these temperature changes is alarming and raises a serious question: if similar regime shifts occur in the future, can viticultural cropping systems adapt fast enough?

- Coinciding with the abrupt temperature increases in the 1980s, sugar concentrations in Napa and Bordeaux began to increase significantly and these increases have continued.

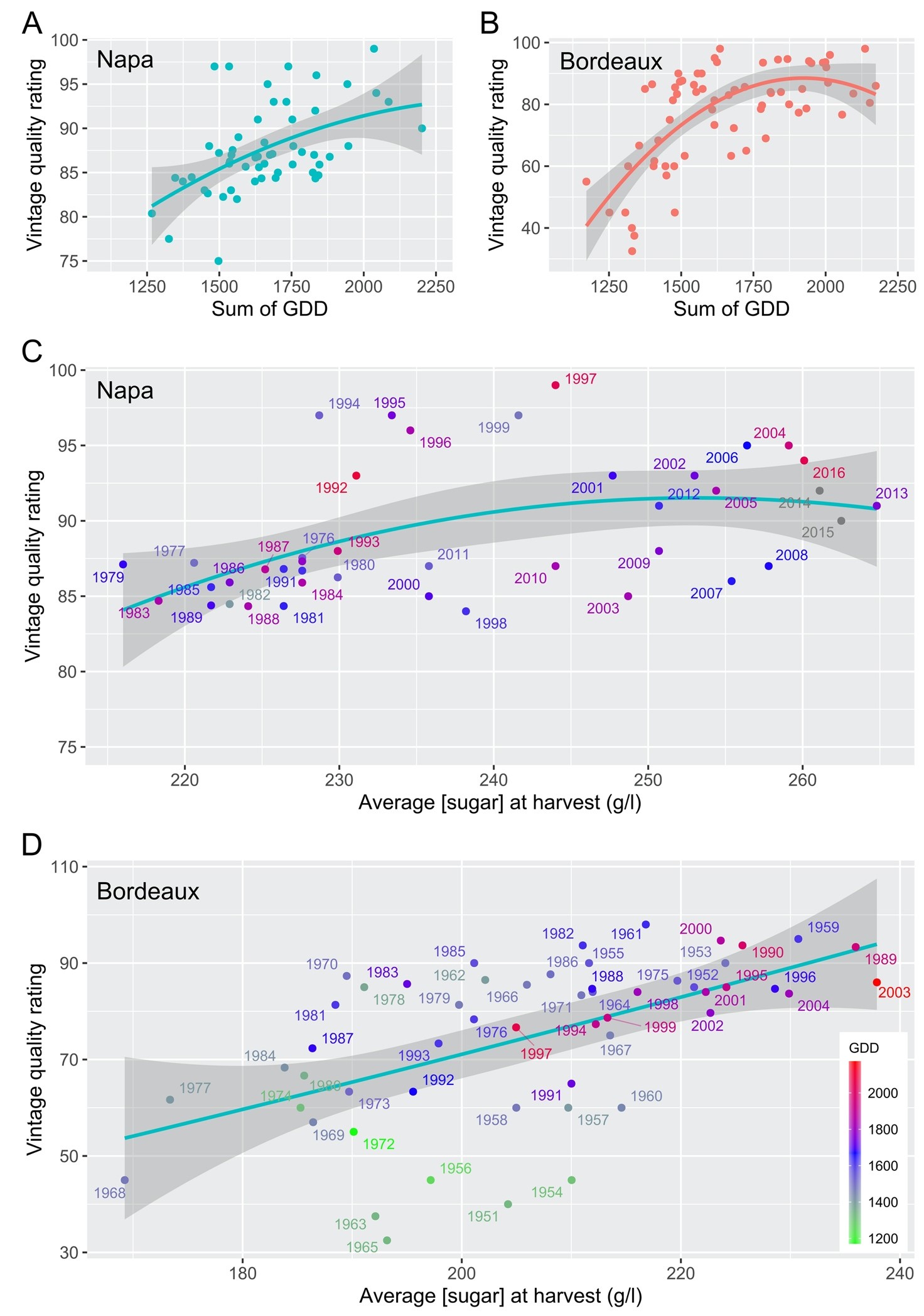

- As temperatures exceeded what was previously considered the optimal average growing season temperature (17.3°C for Bordeaux), the grapes produced better wines. As the graphs (below) show, the observed increases in temperature in the two regions are positively correlated with the average vintage quality rating, although the correlation is much weaker for Napa as it was comparatively warmer than Bordeaux prior to the 1980s.

- Higher temperatures have significantly decreased the likelihood of a poorer vintage and even the warmest vintages do not show any significant decrease in quality. A similar positive relationship exists between fruit sugar concentrations at harvest and quality (C and D above). The idea of a lower temperature threshold is clearly evidenced in Bordeaux where the coolest vintages mostly diverge for the relationship between sugar and quality (D). However, the authors stress that quality ratings are subjective and likely differ between the two regions. “Both regions have had some high-quality vintages at lower sugar concentrations suggesting that high sugar is not tantamount to high quality. What is true is that to date increased warming and riper fruit have not been associated with any loss of wine quality,” the report states. “Instead, higher temperatures have made wine quality more consistently good, perhaps due in part to evolving consumer preference for more ripe flavours with subdued, vegetative aromas and tannin profiles.”

- Higher temperatures can harm grape composition, including colour, taste and aroma. Researchers examined pigment and sugar content of five California vintages of Cabernet Sauvignon, finding that as the grapes got sweeter the skin and colour deteriorated. At sugar levels above 200–225g/l (~21–22 Brix) anthocyanins no longer accumulated and became decoupled from sugar accumulation. Above 250g/l (~25 Brix) of sugar, colour was lost to some extent. Skin flavonols also undergo a marked degradation above similar thresholds. “The degradation of these quality-related compounds and the observed plateaus of wine quality ratings suggest there can be too much of a good thing,” warns the report.

Short-term strategies

Various strategies have been suggested for mitigating the impact of climate change in the short-term. According to this report, these include:- Canopy management to delay the berries’ development cycle. Reducing the canopy area to less than 0.75 m2/kg shortly after fruit set can increase the time from flowering to veraison by approximately 5 days. Other measures, such as late winter pruning (around budbreak), can also delay the onset of budbreak – resulting in a delay in flowering or veraison by up to 5 days.

- Applying ‘sunscreen materials’ to create inert particle films upon leaves, such as calcium carbonate, kaolin and potassium silicate, which can improve plant metabolic growth under heat, drought and radiative stresses. The use of shade nets can also reduce sunlight exposure.

- Supplemental drip-irrigation during inflorescence development and flower formation to offset drought conditions. A study conducted in Mediterranean climates showed the subsurface drip-irrigation system, using the threshold of leaf water potential at -0.4 MPa and -0.6 MPa before and after veraison respectively, was useful in improving grapevine water use efficiency and yield, without affecting grape quality.

- Soil management – limiting soil tillage, growing suitable cover crop species, and applying organic or synthetic mulches (such as compost, bark or straw) to improve soil water retention capacity.

- Being prepared for novel pests and diseases.

What does the latest research reveal about these strategies?

Irrigation

‘There doesn’t need to be a tremendous amount of water for grapes’Another interesting piece of research from UC Davis suggests that California’s coastal grapegrowers could cut irrigation water by half without affecting yield or quality. The findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science, show that vineyards can use 50% of the irrigation water normally used by grape crops without compromising flavour, colour and sugar content.

“It is a significant finding,” according to lead author Kaan Kurtural, professor of viticulture and oenology and an extension specialist at UC Davis. “We don’t necessarily have to increase the amount of water supplied to grape vines.”

A drip-irrigation system being installed at a new vineyard at the UC Davis Oakville Station. (Kaan Kurtural/UC Davis)

Kurtural and others from his lab studied irrigation and Cabernet Sauvignon grape quality at a research vineyard in Napa Valley over two growing seasons, a rainy one in 2019 and a hyper-arid one in 2020.

They focused on crop evapotranspiration, which was the amount of water lost to the atmosphere from the vineyard system based on canopy size. The weekly tests used irrigation to replace 25%, 50% and 100% of what had been lost by the crop to evapotranspiration.

They found that replacing 50% of the water was the most beneficial in maintaining the grape’s flavour profile and yield. The level of symbiotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which help grapevines overcome stresses such as water deficits, was also not compromised. And the water used to dilute nitrogen application was also reduced, making the process more environmentally friendly.

The water footprint for growing grapes also decreased. For both the 25% and 50% replacement levels, water use efficiency increased between 18.6% and 29.2% in the 2019 growing season and by 29.2% and 42.9% in the following dry year.

While focused on Cabernet Sauvignon, most red grapes will respond similarly, Kurtural said. “In the end, drought is not coming for wine,” Kurtural said. “There doesn’t need to be a tremendous amount of water for grapes. If you overirrigate in times like these, you’re just going to ruin quality for little gain.”

‘Drought is not coming for wine’

Shoot trimming

For several years, Spanish professor Martínez de Toda, from the University of Rioja, has been researching ways to mitigate the effects of climate change through targeted shoot pruning. In a trial reported in the Vitis Journal of Grapevine Research, he was able to delay the ripening of grapes by around two months. His technique involved pruning the main shoot above the sixth node at the end of flowering, leaving the leaves, axillary shoots and existing clusters below that. By breaking the apical dominance, rapid side shoot growth is forced on the one or two uppermost nodes. The side shoots in turn form fruits for a second, later harvest. In the trial, the grapes of the main shoot ripened about 13 to 15 days later and the grapes of the side shoots about 35 to 57 days later than those of the unpruned control plants. In terms of quantity, the second harvest was about 30% of the main harvest.

The second crop produced smaller berries with lower pH, higher acidity, higher tartaric and malic acids and much higher anthocyanins compared to primary crop.

The two-year field trial was conducted with Garnacha, Tempranillo and Maturana Tinta vines in a two-arm cordon system. Although longer-term studies are necessary, all indications are that the grapes of this double culture ripen well and that sufficient carbohydrate reserves can also be formed for the following year.

The report says it is “a bold method to fight against climate warming that could be only developed in really warm viticultural regions”. It states the main drawback is loss of yield, but the report also recognises that such techniques require extra manual labour.

Elsewhere, Martínez has said that other canopy management techniques, such as late winter pruning and minimal pruning, can delay grape ripening for 15-20 days.

Timing is important

Researchers in Italy have confirmed that, at least for late-maturing cultivars, the timing of application of late shoot-trimming plays a key role in modulating the intensity of the effects of this management practice on berry composition.Their two-year experiment (reported here) compared the responses of Aglianico grapevines, a late-maturing red cultivar, to shoot-trimming applied at three different stages of berry ripening (at total soluble solids of 6, 12, and 18 Brix) plus a control area of untrimmed vines.

The study concludes: “Independent of the application timing, shoot-trimming decreased berry total soluble solids at harvest below that of control vines, but the later the shoot-trimming was applied, the lower berry total soluble solids was at harvest. Shoot-trimming did not affect other berry parameters.”

Long-term strategies

Long-term adaptation strategies, according to this report, include:- Changing training systems. The gobelet training system, for example, can reduce crop water demand by lowering the leaf area per hectare and limiting the demand for photosynthesis and transpiration. The semi-minimal pruned hedge can delay bunch rot formation and fruit maturity. Increasing the trunk height on dry and stony soils can avoid the impacts of excessively high temperatures in the fruit zone.

- Changing the clone or rootstock. With most grape varieties there are still differences in maturity timing of 8 to 10 days for different clones of the same variety. Late-ripening clones can be grafted onto the same variety, so that the wine typicity will not significantly change and the fruit ripening process can be delayed. Rootstocks such as 140 Ruggeri and 110 Richter are highly drought-resistant. Recent research suggests new rootstock M4 can enhance plant tolerance to water stress.

- Changing the variety. The cooler northern European winemaking regions can choose from the varieties currently available in southern Europe, whereas the latter should consider planting late-ripening varieties or new varieties with drought and heat tolerance.

- Changing the site location. Relocating to cooler coastal areas, to sites with higher elevation, latitude or less sun-exposed locations, such as north-facing slopes, are options generally considered as a last resort. But Dr Alessandro Dell’Aquila, a climatologist at the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development, advises winemakers to act now. “Winemakers should start thinking now where they can buy new plots of land and start planting grapes as an investment for the next 10 or 20 years,” he says in an article published in Horizon, the EU Research and Innovation magazine.

.png)